Creative and Intellectual History

On Conferences, Service, and Advancing Caribbean Women’s Writing

The Association of Caribbean Women Writers and Scholars (ACWWS) was formed in 1994-1995 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, following the landmark 1988 Caribbean Women Writers conference organized by Selwyn Cudjoe at Wellesley College, USA. This conference created an awareness of the number of Caribbean women writers and generated a volume dedicated to celebrating their presence. M. NourbeSe Philip synthesized the significance of this event in the film Caribbean Women Writers when she describes her experience attending this first conference:

Language is so difficult at times to find the right way to express that sense of being among all these women from the Caribbean, Africa, Asia. There [were] some white women, some Chinese, but just to be among this gathering of women, who were all involved in different ways but in the same project that is voicing what has been unvoiced, at least in terms of literature for such a long time.

NourbeSe Philip’s statement indicates a common assumption from that period: that a small number of Caribbean women were only writing. Women’s writings were barely taught and discussed in the early phase of the field, and few works by women were even published until the late 1970s. Male Caribbean writers dominated Caribbean creative writing and scholarship. While this is not to diminish the contribution of male writers and critics, the fact that Selwyn Cudjoe, a male scholar, organized the first Caribbean women’s conference and edited the first volume of Caribbean Women Writers speaks to Caribbean women’s lack of visibility and influence in academia as late as the eighties. The 1988 conference and those organized in the subsequent years allowed Caribbean women writers and scholars to experience each other’s presence and reshaped Caribbean literary intellectual discourse.

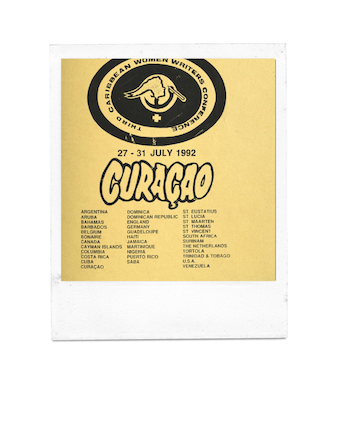

After this first gathering, Helen Pyne-Timothy (ACWWS’ founder and inaugural President) planned a second conference in the Caribbean at the University of the West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, in 1990. Unlike the first conference, which mainly focused on Caribbean women writers’ readings, the 1990 gathering featured the voices of Caribbean scholars critically discussing the writers’ works. The third conference spearheaded by Joceline Clemencia in 1992 at the University of the Netherlands Antilles, Curaçao welcomed many participants from the Hispanophone and Dutch-speaking areas of the Caribbean–an important gathering since a larger number of Anglophone Caribbean writer’s presence dominated both of the initial conferences. Still, it was also at this gathering, as Helen Pyne-Timothy writes in the Spring 1996 newsletter, that “the organization of the Conference became mired in serious difficulties, and it seemed that these wonderfully stimulating events would cease to occur.” While Cudjoe, Pyne-Timothy, and Adele Newson planned for the continuation of the conferences, Pyne-Timothy, Brenda Berrian, Carole Boyce-Davies, Jacqueline Brice-Finch, and Tanya Saunders (and later joined by Vicki Silvera) “came together at their own expense” to form ACWWS. One more conference was held at Wellesley College in 1995, but the first conference under the organization's umbrella was in 1996 at Florida International University, USA.

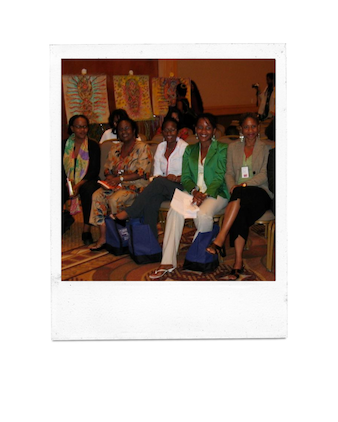

In response to the absence of access and knowledge on Caribbean women’s literary writings and scholarship, ACWWS began working on many objectives, which they carried out with their service to the profession via conference and journal work. For instance, the 1998 conference at the Renaissance Resort in Grenada featured the launch of the first volume of the Association’s journal, MaComère, created to support their most pressing goal: “to provide a forum for the advancement of the critical study and teaching of the works of Caribbean women writers and scholars.” In the Fall & Winter 1999-2000 newsletter, Carole Boyce Davies invites us to consider how the “journal [was] fast becoming the place to which one can turn for the latest intellectual and creative work on and by Caribbean Women Writers.” Similarly, the ongoing efforts of conference work intended to “provide access and knowledge of the work of Caribbean Women Writers in the language areas of the Caribbean.” Other places where these conferences have occurred are the University of Puerto Rico-Mayagüez (2000), Université des Antilles et de la Guyane, Campus de Schoelcher, Martinique (2002), Hotel Lina and National Library of the Dominican Republic (2004), Florida International University, USA (2006), St. George’s University, Grenada (2008), Louisiana State University, USA (2010), Teachers Training Institute, Suriname (2012), University of Kansas, USA (2018), virtually on zoom during Covid-19 (2021), and most recently the University of Costa Rica, San José and Limón campuses (2023).

This story depicts how ACWWS’ institutional history challenges the assumption that most writers and scholars work alone and that service should be at the bottom of the list for academics. From attending to a community’s need to conference work and service to the profession, these women’s trajectories and efforts are noteworthy in creating coalition-building that pushed toward radical world-making in Caribbean literary studies. Indeed, the history presented in this digital archive serves as a reminder that women’s labor in the profession transformed the field of Caribbean studies and influenced cross-cultural connections between Caribbean women’s creative and intellectual communities.